Did you know that in the early 20th century, there was a thriving community of Black-owned businesses in Oklahoma? This close-knit community of about 10,000 resided on the fringes of Tulsa. At its peak in 1921, it contained all the components of a self-sustaining economic engine.

Businesses sprung out of demand from growing wealth within the community. This allowed enterprising individuals to establish networks to accelerate this growth. Further capital funding, specialization from high-quality local education, and a “buy local” mantra were the accelerant.

The area, which had become known as “Black Wall Street”, featured the largest Black-owned hotel at the time. It also had some 600 businesses and all manner of professional service providers.

Naturally, it had its own all-star entrepreneur we might think of as the Bezos of Black Wall Street.

Today, I want to look at the economic side of Black Wall Street and to discover what exactly made it special.

I’ll answer:

- Why was it called Black Wall Street—was there a segregated stock market?

- How did it become a haven for Black entrepreneurs from across the country?

- Why isn’t there a historic center of Black wealth today in Tulsa with names like Rockefeller, Carnegie, or Ford?

First, let me give you a little context for how Black Wall Street came about.

The Founding of Black Wall Street

In the late 19th century, Oklahoma participated in a land run—a time when the territory opened up land for claiming and homesteading with the removal of Native Americans.

Mr. O.W. Gurley

O.W. Gurley, originally a teacher and postal service worker from Alabama, moved to Oklahoma and staked a claim in the 1889 land run.

Once he settled in, Gurley found some success in teaching and the operation of a general store in Perry, Oklahoma. However, he had his eyes set on bigger fortunes and sold his store in 1905. Oil was booming in Tulsa and Gurley purchased 40 acres of land at the edge of town.

![1890 "Proportion of the colored to the aggregate population" data map—highlighting Tulsa, OK [Source: US Census].](https://www.tictoclife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/us-1890-census-map-colored-population.jpg)

At about the same time, Oklahoma gained statehood within the United States. One of its first actions was to pass a set of Jim Crow-style laws which enforced segregation.

Gurley persisted with his entrepreneurial dreams and opened his first business on a trail near the railroad tracks on the north side of Tulsa. It was a rooming house which became popular with Black migrants fleeing oppression in Mississippi. The trail by the railroad tracks became known as Greenwood Avenue, matching the name of a city in Mississippi.

Eventually, Gurley’s wealth grew, and along with it his businesses. He added five residences, multi-story apartment buildings, and an 80-acre farm. He began splitting up his original 40-acre tract to other Black entrepreneurs.

The Greenwood District

Soon, the area became known as the Greenwood District. Eventually, it comprised multiple streets, businesses, and a growing population. It benefited from a collectivist economy that didn’t need to worry about segregation prevalent in the rest of Tulsa.

Gurley’s influence in the area grew as he provided loans to other Black entrepreneurs in the area to start their own businesses.

The labor force of the Greenwood district, when not working within the district, provided services to neighboring Tulsa and regional communities. With the oil boom, wealth blossomed and provided for the demand of domestic services often fulfilled by the Black laborers in Greenwood.

Business grew in Greenwood as wealth created the demand for ever more services and luxuries.

How did the name Black Wall Street come about? The wealthy populous of Greenwood eventually earned the nickname “Black Wall Street” after a visit from Booker T. Washington.

Was there a segregated, Black stock market? No. Black Wall Street earned its name as a reflection of the wealth and business development in the Greenwood District.

Was there lots of banking on Black Wall Street? Greenwood wasn’t significantly known for banking, though banks were in the district and loaned to Black-owned businesses which often had difficulty obtaining credit through traditional institutions.

In fact, it was a different community that also became known as “Black Wall Street” which was famous for its banking innovation. Maggie L. Walker was the first Black woman to charter an American bank. In 1903, Penny Savings Bank opened in Richmond, Virginia as part of another wealthy Black enclave.

At its height, Greenwood and Black Wall Street turned Gurley into a tycoon of sorts with more than 100 businesses catering to the needs of Greenwood’s residents.

The Business of Black Wall Street

What ended up becoming Black Wall Street’s strongest asset was what necessitated its creation in the first place. Segregation meant Black residents were unable to participate in economic activity throughout Tulsa in the same way the rest of the city could.

Today, we think of “buy local” as a piece of marketing to support our respective downtowns, historic markets, and areas of commerce.

But at the time, legal segregation forced Black residents to either do without services, products, and luxuries or…well, to create their own. And that’s precisely what Greenwood did.

PBS conducted a fantastic set of interviews in 1993 with folks who lived in Greenwood. Their stories color what Black Wall Street had become, and how:

It was an insular Black community that existed out of necessity and reflected what I call an economic detour. In other words, people couldn’t engage with the mainstream economy. They were shunned and turned away. They created their own ancillary economy in a particular geographic space because of Jim Crow segregation. It was successful because even people who worked outside the community brought their money back and spent it in the community.

Hannibal B. Johnson

In a case of turning some abhorrent lemons into lemonade, Greenwood’s residents promoted each other’s businesses. The velocity of money—economic activity—was high within Greenwood and a dollar spent would cycle dozens of times amongst Black-owned businesses before it’d exit the area.

[Y]ou could get anything you needed, it was there. I like to tell the story of someone coming to my [doctor’s] office paying two dollars, and my going down to the Busy Bee Cafe and eating and paying 90 cents. And then the girl at Busy Bee going over to McGowan’s to buy some hose. McGowan was going to buy his prescription at the pharmacy. Bowser going down to McKay’s and getting his pants pressed. The man from there going over to the Black dentist, all within a one and a half block area. A dollar perhaps turned over 12 or 13 times.

Dr. Charles Bate

Greenwood really did have their own version of every service, luxury, and producer a family in the early 20th century might need access to.

List of businesses in Black Wall Street

How many businesses did Black Wall Street have? About 600.

I pulled names and professions from a historical document on Black Wall Street and there are countless different types of services on offer.

Here’s a small selection of the near 600 businesses:

- R. T Bridgewater, Physician

- Mrs. L. Charleston, Grocery

- Mrs. G. W. Hunt, Beauty Parlor

- Leon Williams, Confectionery

- F. R. Williams, Real Estate

- Rev. J. H. Hooker, Photographer

- J. L. Mosley, Shoemaker

- J. W. York, Meats

- Cornelius Hunter, Restaurant

- Mrs. Bertha Brown, Restaurant

- T. B. Carter, Billiards

- Caver French, Dry Cleaners

- T. D. Jackson, Barber

- Dr. L. N. Neal, Chiropractor

- Mrs. Dora Wells, Garment Factory

- W. D. Keley, Lunch Counter

- S. G. Smith, Insurance

- Bashears & Franklin, Attorneys and Oil Dealers

- Oquawka Cigar Store

- Bayers & Anderson, Tailors

![Booker T. Washington High School in the Greenwood District, 1920 [Source: OHS].](https://www.tictoclife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/greenwood-district-high-school-booker-t-washington.jpg)

Greenwood boasted its own school system, hospital, and several churches.

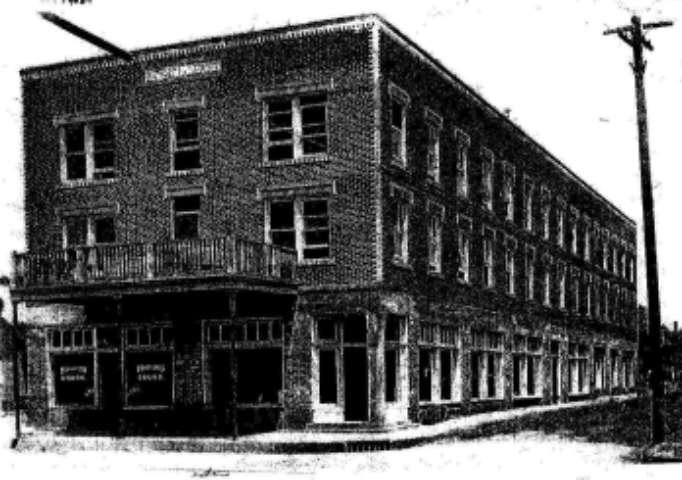

The 54 room Stradford Hotel rivaled the luxury of any hotel in the greater Tulsa area.

Silent films and piano performances found large crowds at the 750-seat Dreamland Theatre.

The day’s events were captured by two newspapers.

Greenwood thrived.

Minting “Millionaires”

The proprietors of Dreamland Theatre became the owners of the first car in Greenwood at a cost of more than $50,000 in today’s dollars.

![Williams Family in their 1911 Norwalk. [Image source: Tulsa Historical Society]](https://www.tictoclife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/dreamland-theatre-first-car-greenwood-district-black-wall-street-1911-norwalk-ths.jpg)

Their theater and related businesses were valued at about $1.2M in today’s dollars ($85,000 in 1921).

In its heyday, the Greenwood District covered about 40 square blocks with Greenwood Avenue stretching more than a mile through the heart of Black Wall Street.

A half dozen private planes were owned by Greenwood residents. Yes, airplanes.

J.B. Stradford’s empire, which included the largest Black-owned hotel in the US, and palatial home were valued at about $2.5M in today’s dollars ($175,000 in 1921).

By the time O.W. Gurley’s empire reached its zenith, it was estimated to be worth between $7M and $14M in today’s dollars ($500,000 to $1M in 1921).

The Greenwood District was where African Americans could escape segregation that locked them out of the economy and create wealth within their own economic system, supported by people attempting to scratch out a living just like them.

The Greenwood District paved the way for similar segregated communities that came later, like American Beach in 1935 on Florida’s coast—which I recently visited. The community became home to people of color seeking an escape and recreation, eventually becoming a cultural cornerstone. It had its own infamous founder, A.L. Lewis, and powerful icon that promoted living with nature and a minimalist lifestyle—The Beach Lady. She had a doctrine for life that those of you interested in achieving financial independence should get behind!

What Happened to Black Wall Street

Using O.W. Gurley as the exemplary business magnate of Black Wall Street, Henry Ford is estimated to have been worth about $100M at the same time Gurley was worth nearly 1% of Ford.

1% doesn’t sound like a lot until you consider that Ford was the wealthiest person alive only a few years later. Consider that 1% of the wealthiest American today (at around $200B for Bezos or Musk) would equate to $2 billion.

Using one of our favorite FIRE measurements, what would have happened if Gurley dumped about $750K into the S&P 500 in 1921 and his heirs reinvested the dividends?

It’d worth about $18.6 billion today!

The wealthiest African American today is Robert F. Smith. Through his private equity firm, Smith has built a net worth of about $5.2 billion.

Gurley rapidly grew his wealth through entrepreneurship across Black Wall Street. And there are countless examples of other business leaders creating wealth for the Greenwood District.

Here’s an historic map of the Greenwood District circa 1921:

![The yellow section represents historic Greenwood. You can spot the southern terminus at the railroad tracks where O.W. Gurley started his first rooming house. [Source: National Park Service]](https://www.tictoclife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/1921-greenwood-district-map-black-wall-street.jpg)

But, here’s Black Wall Street and the Greenwood District today from overhead:

The bustling urban center of Greenwood, Black Wall Street, is nowhere to be seen. Instead, there’s a sprawling university campus on the northern stretch. A large sports stadium rests to the west. And a highway bisects Greenwood Avenue running east-west.

What happened?

1921 Tulsa Race Massacre

Sadly, I was exposed to the events of Tulsa’s Black Wall Street massacre by HBO’s premiere episode of Watchmen in 2019.

Not from a textbook or a history class. From TV.

I’d heard the phrase Black Wall Street in an economic context years before and took some vague interest in what it portended.

I’d assumed that HBO’s presentation was some sort of extreme dramatization of events.

After all, Watchmen plays with historical timelines.

The shot below is part of the scene from the show that describes the attack on the main strip of Black Wall Street, which in real life, is Greenwood Avenue.

![Watchmen premiere: "It's Summer and We're Running Out of Ice". The episode depicts the massacre on Black Wall Street in Tulsa, 1921. [Dramatization—fictional image, source: Watchmen]](https://www.tictoclife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/watchmen_e01_01-black-wall-street-massacre-screencap.jpg)

The scene plays out with numerous casualities.

I think the word—casualties—is appropriate. It’s usually used in the context of military battles and war zones. And the depiction isn’t too far from a war zone.

Hell, there’s an airplane flying down the street dropping bombs.

This is a depiction of a section of an American town in 1921. It’s Tulsa, Oklahoma.

But the thing is, the depiction isn’t actually that far from the truth.

A real massacre did occur—the Tulsa Race Massacre—and real Americans did die.

Eyewitness reports from the time claim private planes were used to drop improvised firebombs on the buildings and businesses of Black Wall Street.

The aftermath

In fact, at least 36 deaths were confirmed with death certificates. Estimates place the total number of deaths at closer to 300. The wide range is due to potential mass burials occurring.

The City of Tulsa has discovered what they believe to be one mass burial site containing “at least 12 individuals”. The work is ongoing with an update as recently as late 2020.

This matches the American Red Cross’s original 1921 estimate of “55-300” deaths.

No matter the case, the Tulsa Race Massacre on Black Wall Street reflects a horrific event of carnage exhibited by Americans upon other Americans. It left part of Tulsa looking like the Western Front in a World War that ceased only a few years prior.

Below is a very real image of just a piece of the destruction.

![The destruction of Black Wall Street during the Tulsa Race Massacre, 1921. Image: Standpipe Hill destruction [source: OSU Digital Collections].](https://www.tictoclife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/black-wall-street-massacre-standpipe-hill.jpg)

The cause

I don’t intend for this article to be about why the destruction of Black Wall Street occurred. You can find lots of great articles about how it happened across the web and numerous historical photos of the aftermath.

It’s sufficient to say that a coordinated, extremist mob fueled by racial hate, jealousy, and resentment attacked the Greenwood District.

Black Wall Street was left in cinders and dirt.

The burning of Black Wall Street’s economy

While much ink has been spilled about the societal and civil situation that triggered the massacre, I wanted to highlight the economic cost for the community.

Remember that the Greenwood District and Black Wall Street came about to relieve economic anxiety and give hope for an American Dream to Black residents.

I worked through Mrs. Mary E. Jones Parrish’s excellent first-hand documentation, “Events of the Tulsa Disaster“, to identify the economic losses the community undertook.

Parrish painstakingly documented the claimed financial losses of the district’s residents.

Loss of property

As an example, I’ve digitally translated a section of her “partial list of losses” which focuses on property ownership losses below.

| Property Owners | Losses ($) |

|---|---|

| Mr. Jim Cherry | 50,000 |

| Mr. O. Gurley | 65,000 |

| J. H. Goodwin | 30,000 |

| Mr. John Gist | 25,000 |

| Dr. R. T. Bridgewater | 32,000 |

| Mrs. Lula T. Williams | 85,000 |

| Mrs. Annie Partee | 35,000 |

| Mrs. Jennie Wilson | 25,000 |

| Mr. A. Brown | 15,000 |

| Mr. J. B. Stradford | 125,000 |

| Mr. A. L. Philliips | 40,000 |

| Mr. W. H. Smith (Welcome Grocery) | 40,000 |

| Elliott & Hooker, Clothiers and Dry Goods | 45,000 |

| Dr. A. F. Bryant | 30,000 |

| Mr. C. W. Henry | 25,000 |

| Jackson Undertaking Co. | 15,000 |

| Mr. T. R. Gentry | 25,000 |

| Prof. J. W. Hughes | 15,000 |

| Mr. S. M. Jackson | 15,000 |

| Total | $737,000 |

You might recognize a name or two in the list, Mr. J.B. Stradford—the hotel proprietor—appears with a $125K loss.

In total, these property owners claimed a $737K loss.

Loss of businesses and residences

Numerous small businesses resided in shared space provided by these property owners.

Parrish further itemizes $934,880 worth of small business and personal residential property losses. These losses reflect things like the small grocer’s food stocks. Or the physician’s instruments for analysis and surgery.

It’s all the hardware, tools, and machinery to run an independent economy.

Below is just a little description from Parrish that exemplifies the countless losses for small businesses.

Mr. Henry Nails and Mr. J. H. Nails are two of Tulsa’s leading businessmen. Before the disaster, they owned a modern shoe shop equipped with all machinery needed to conduct a high-class shop. Their loss was estimated at over $4,000 at 121 N. Greenwood.

Mrs. Mary E. Jones Parrish, Events of the Tulsa Disaster

The beating heart of Black Wall Street’s economy—small businesses—were snuffed out, taking with them the hope of the Greenwood District.

Loss of community infrastructure

Lastly, Parrish itemized losses to the larger organizations in the area: schools, churches, and the hospital.

These are the organizations that formed the glue within the community.

| Organization | Type | Losses ($) |

|---|---|---|

| Dunbar Grade School | School | 20,000 |

| Methodist Episcopal | Church | 1,000 |

| African Methodist Episcopal | Church | 2,500 |

| Colored Methodist Episcopal | Church | 2,000 |

| Mt. Zion Baptist | Church | 6,500 |

| Paradise Baptist | Church | 85,000 |

| Metropolitan Baptist | Church | 3,000 |

| Union Baptist | Church | 2,000 |

| Seventh Day Advent | Church | 1,500 |

| Frissell Memorial | Hospital | 3,500 |

| Total | $127,000 |

Through the destruction of these community centers, the fabric of the community network was unwound.

Total losses

In total, Parrish recorded $1,798,880 in claimed losses from residents and concluded it was only a partial list.

It’s estimated that some 1,200 residences were burned—most of which were difficult to value or poorly documented.

In the summer of 1921, The American Red Cross conducted their own analysis and reporting. Their conclusion?

Property losses including household goods will easily reach the four million mark. This must be a conservative number in view of the fact that lawsuits covering claims of over $4,000,000 were filed up to July 30th.

The American Red Cross, Disaster Relief Report

Adjusted for inflation, that’s $55 million in direct economic destruction suffered by the residents of the Greenwood District.

That doesn’t include the loss of life. It doesn’t include the cost to move to a new place, restart your business, or the productive work lost in doing so. It doesn’t account for the incredible emotional or mental cost of seeing the productive labor of your friend’s, your family’s, your neighbor’s work set ablaze and burned to the ground overnight.

One recent academic study of the economic cost estimates the value closer to $150-200 million.

A fight for recovery

To this day, decedents of Greenwood residents fight to be reimbursed for their losses and for some form of reparations. Why? Because even insurance denied their claims.

Insurance often included a stipulation that claims wouldn’t be covered in the event of a “riot”. And so, the Tulsa Race Massacre was known as the Tulsa Race Riot for decades.

Only in recent years has it been properly relabeled:

As a legal matter, if the Oklahoma courts had agreed that the event was a massacre, the insurance companies might then have been forced to pay compensation to the victims.

The Destruction of Black Wall Street, The American Journal of Economics and Society

While the City of Tulsa did end up reimbursing residents for about $130K in damages, insurance payments were minimal and residents were never made—even remotely—whole again.

From 1921 to Today

After the Tulsa Race Massacre, residents tried to rebuild despite losing nearly everything and being reimbursed almost nothing.

Black Wall Street did see a revitalization for a time. Residents who survived the massacre and returned to Greenwood rebuilt much of the district. Within ten years, it was recognizable again as a vital Black community.

The 1950s-today and desegregation: By the time the 1960s rolled around and Tulsa was desegregated, urban planners were looking for an opportunity to reenvision the city.

Through infrastructure construction and eminent domain, Black Wall Street in Tulsa was lost once again. Sliced up by the highway visible in the overhead photo above, modern-day Black Wall Street is a shell of its former self with only a few Black-owned businesses in the area.

Gurley and Black businesses: O.W. Gurley didn’t surface in history again after the loss of his economic vision that was Black Wall Street. Records are slim, but it’s suggested he moved to Los Angeles with his family and lived a fairly simple life.

The numerous Black entrepreneurs who found their start in Greenwood don’t seem to come up in history in significant ways again.

If not for their tremendous losses, one would expect to find dynastic family empires coming about from the opportunities for Black families in Greenwood.

Lessons of Black Wall Street

The greatest economic privilege I have isn’t in my talent or abilities. It’s not my smarts.

The thing that made it possible for me to achieve financial independence at such a young age is precisely what Black workers were building in the Greenwood District.

It’s a network and community that will lift me up. They’re the source of my upbringing, education, and success.

A network to wealth

Throughout my life, I’ve known a community that would be there for me when I need them.

- My family raised me and provided me with a quality education

- Friends supported my interests and guided my decisions

- Teachers and mentors propped up my talents while acting as character references

- Professional colleagues served as accreditors for my claims

More than that, they acted as a backstop.

I knew that if I really screwed up, there were a handful of people I could call day or night for $10K in bail money.

If I were to start a business and needed funding, “Friends and Family” funding would be there for me.

Community: Black Wall Street’s investment

Nearly 100 years ago today, the Greenwood District and its Black Wall Street reached its pinnacle point of Black empowerment and wealth.

Black Wall Street wasn’t about the stock market of investment banking.

Black Wall Street was a network of people working with each other to form the relationships you need in America to create successful businesses.

Greenwood’s neighbors were its funders, its customers, and its marketing plan.

It was a collective trying to right a legal, ethical, and moral wrong in the best way it knew how—by working together.

Were you familiar with Black Wall Street and the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921?

What do you think your greatest economic privilege is?

Let me know in the comments!

Black History Month 2021

In honor of Black History Month during February, we’ve been running a poll on TicTocLife asking you the reader to help us pick which charity for racial equality to donate to. If you have a moment, read through the four charities we suggest and vote in our poll.

We’re featuring:

- National Urban League

- Thurgood Marshall College Fund

- Virginia Center for Inclusive Communities

- National Black Farmers Association

You can read a summary for each of these charities and vote in our poll right here until March 1, 2021 [update: now closed].

You’ll help direct our monthly donation, raise awareness about the charities, and maybe even find a way to help give back to other communities.

![The businesses of Black Wall Street in its heyday [Image source: America in Color: The 1920s, Smithsonian].](https://www.tictoclife.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/black-wall-street-tulsa-1200x675.jpg)

10 replies on “Black Wall Street and the Business of Creating a Community”

It’s really incredible that they don’t teach this stuff in school. I think I learned about it on HBO show (Watchmen?) last year and had to look it up. My reaction was “why don’t I know about this!?” Absolute gut punch to the individuals involved and the community as a whole.

Yep, I mentioned the same thing re: Watchmen in the post! ? Pretty wild that such an event doesn’t seem to be more well known within the general population!

Tulsa resident here. I applaud your research on this topic, but your intro was a bit cringe-worthy. “Of all places, Tulsa”. Words like that, spoken from such a platform as this, from a person who I dare say, has never visited this town. Who appears unfamiliar with Oklahoma’s – and Tulsa’s – complicated history on race and economy. Well, it reveals a level of well intentioned ignorance that’s hard to read. Come visit, of all places, Tulsa, before passing judgement that a such a gem, as Black Wall Street was, could have grown here.

Hey Katie! I greatly appreciate the feedback.

I understand your point and will slightly adjust the phrasing to better align with my intentions.

Here’s a map from the US Census in 1890 of the Black population across the US:

https://www.census.gov/history/img/statab1890.jpg

While the surrounding corners of Texas and Arkansas had significant Black populations, there’s an immediate drop off at the border of Oklahoma. As should be no surprise, most of the Black population of America in the post-Civil War era resided further south and out to the east up through Virginia (my neck of the woods).

I don’t think it’s unfair to say that, to the average observer, Oklahoma isn’t where you’d expect to find an emergent Black enclave of wealth at the turn of the century. Reinforcing this point, as I briefly touched on in the article, Oklahoma’s first actions as a state (Senate Bill Number One) enshrined segregation with legal enforcement in 1907. Even as a territory, Oklahoma had already taken similar actions to enforce segregation (1897 Oklahoma Territorial Legislature).

My focus was more on Oklahoma than specifically Tulsa, which is reflected in the minor text update I’ve made to the piece. I’m curious if you think that better reflects history and the general point of view of the average person outside of Tulsa.

Today’s Tulsa, I’m certain is much different from the segregated city of 1921. I hope we can visit in the future.

Wow I had no idea that part of history existed. It’s not something that’s pretty well taught in schools, either. Maybe it was taught in Oklahoma.

It’s amazing what race fueled motives can drive a group of people to do. The community wasn’t doing anything to hurt others, they were just doing things to better themselves. And they got punished for it!

I’m fortunate to have come from a middle class family. I haven’t known the struggles of not being able to afford the basic necessities in life such as food and clothes. I know I came from a highly privileged background and I have to be thankful for it!

I suspect most of us clacking away on keyboards would find it hard to relate to the life folks led in this community. Hell, today’s income inequality suggests that poverty in the US is still hard to relate to.

Don’t feel bad, you’re not alone.

We still have a lot to learn.

Cool article Chris. Right on for shedding some light on something that isn’t talked about too much. I always like a good history article coupled with PF. The most tragic events in our history are the things we should study and focus on the most so we never forget.

Me too, so I probably wrote this one for me. And maybe hoping to catch one or two folks who weren’t familiar. I know it’s not a happy topic that folks will share and enjoy, but sometimes those lessons aren’t happy ones.

And to your point, sometimes they’re the most important.

There are many other instances that aren’t covered in the history books very much that have some similarities. The members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were forcibly removed from their homes in Illinois and never received compensation. Governor Boogs of Illinois even went as far as to issue a Mormon extermination order. They gathered together in Salt Lake City and supported one another by buying locally from other LDS owned businesses. That community went on to thrive even in the present day. It is sad to see that history shows us that our government leaders aren’t willing to stand up and fight against oppression. Hopefully we have learned from these events.

Much respect for this info. . Coming from North Tulsa , GROUND ZERO, these facts were not in our History books …and to this present day the history is still not in the history books . I am going to spread this link along with my stories that I heard from the kitchen table and share them all over the world . I have an obligation ….I AM A DESCENDANT OF BOTH THE CREEK AND CHEROKEE NATIONS AS WELL A DESCENDANT OF A BUSINESS OWNER ON BLACK WALL STREET . NEALS JEWELERY .