I’m going to rip the bandaid off for this article and hit you with the facts right now. I attribute more than half—about 58%—of my spending during my final traditional working years as my personal “cost of working”. The other 42%? That was my cost of living.

Do you know how much you’re spending just to enable yourself to maintain the job you have now? What does it cost to meet all the expectations of your employer, to commute to your office, and to take the consumptive shortcuts you feel you have to in order to stay sane and continue the toil?

What’s your cost of working?

I’m going to lay out how I came to my own conclusion—that 58%—and show you how to calculate your cost of working. It might just be a little enlightening.

Cutting Your Cost of Working

Jenni and I have written quite a bit about our total spending and income over the years. We wrote a chronology covering the 12 year period from when we completed our undergraduate degrees (2006) to when we first became millionaires and shortly after, reached financial independence (2018). At the bottom of this timeline, as Jenni earned her doctor of pharmacy and took on student loans, we were over $100K in debt.

Despite this, ten years later we were millionaires and financially independent.

Today, I want to zoom in on that period when the debt was the deepest and as we began to really change our financial lives. And this time, I want to peel back the curtain a little and show you my own spending craziness at the peak of my corporate employee experience.

While my first professional job in my field was in 2007 (with a $42K salary), I didn’t reach the apex of my employee experience until the end of 2011. By that time, I was making $100K/year. Pretty good for a guy with a bachelor’s in interpersonal communication.

And sure, one of those years would have qualified me for all sorts of poverty-level assistance (less than $13K for 2009!). But, I spent a chunk of that year traveling and preparing for the Peace Corps, then living in Nicaragua with an incredibly low cost of living.

Still, I averaged about $57K/year in income over my professional employee life. The big bump I earned after the Peace Corps came from moving to the DC area and getting deeper into the digital strategy field.

I’ve regaled you before with some of my stories working for a Beltway bandit, like that time I finally put my FU money to use and was escorted out of the building.

With that stage set, let me hit you with some numbers about my cost of working during this period.

In the last couple of years of my employee experience, I routinely had monthly alcohol & bar expenses over $100.

Chalk up another $350 per month for restaurants.

Don’t forget another $4,000 or so on work-related clothes in that period.

Suits. Dress shoes. Belts, cufflinks, and OCBD shirts.

Oh, sorry, “OCBD” not ringing any bells? You probably didn’t find yourself in a traditionalist, conservative working environment where every male donned the same requisite outfit. That’s a dark-colored suit (navy being the most common), black welted dress shoes, an Oxford Cloth Button Down shirt—there’s our “OCBD”.

Of course, there are a few other pieces to the costume, but you get the picture. Professional attire in a conservative work environment gets real expensive, real quick, for both men and women. Purses and heels, watches and ties.

Despite trying to cut corners—I shopped at a Filene’s Basement—clothing expenses really added up for me during this period. Don’t forget the dry cleaning and tailor bills, too!

And don’t even get me started on my $1,500/month rent (that’s WITH a roommate!)—one of my worst cases of lifestyle creep during this time.

Feeling important and worth it

While I could have tried to be the outlier in the office that managed to keep his job, all too often people just want to coast and stay under the radar. That meant matching my peers both in style and action. Lunches out with the team frequently and an outfit to match the environment. When projects were behind and late nights ahead, it was time for happy hours in the city after clocking out.

All this added up. But, I shouldn’t suggest I didn’t want to do these things—I enjoyed this period of my life. I didn’t seek out financial independence and [our current transition to] retiring early because I “hated work”. I’ve found my field challenging and its generally allotted me a lot of flexibility.

Slapping on a suit and getting taken out to oysters and scotch at Old Ebbitt by a colleague makes you feel a little important.

It’s nice.

Those late nights, the commuting, office politics—it all adds up though. Making work-life bearable often meant taking shortcuts that cost money to free up more time for me.

I did less of my own car maintenance. Prepared foods were my nutrition solution. I paid someone else to do chores and tasks I might have done myself with more free time.

In my head, there was a sort of arbitrage at play. If I could work and get paid more per hour why not pay someone else a bit less to do things I didn’t want to do?

In reality that’s often a false dichotomy. You can’t work an unlimited and infinitely flexible number of hours. And perhaps sometimes those chores or tasks needn’t be done in the first place.

How much does it cost to work?

There are real costs to choosing to work rather than to do some other productive activity in your life. A great example of this for a lot of people is childcare. Perhaps a parent can earn $2,500/month working if they pay for daycare at $1,500/month. That’s an easy $1,000 in your pocket, right?

Well, don’t forget you’re effectively deciding to work for $1,000/month, and whatever effort or time that requires, rather than the total $2,500 since it’s now “costing” you $1,500 to work. When considering your cost of working, you might be working for minimum wage! Then again, for some, it’s a necessity to make ends meet. This is all aside from an argument that might be made about the relationship you have with your child when you’re around more.

Therapeutic spending

What about therapeutic spending? There’s the “I deserve it” attitude that comes from working hard and being away from home. Exhaustion takes a toll and we often feel like we deserve that new gadget or a special night out.

These consumptive bandaids add up.

I know I often fell prey to this mentality. And like my work, it’s not as if I didn’t enjoy those nights out. Getting to see live performances at the Kennedy Center was special. Meaningful. I don’t regret it.

But, you have to ask yourself: would I still be doing this [or buying that] if I wasn’t doing this job? If I wasn’t stressed and tired? Do I live where I do because I’m happy here or because this is where I work?

My cost of working

I can tell you whether or not my spending was dependent on where and how I worked in a single chart.

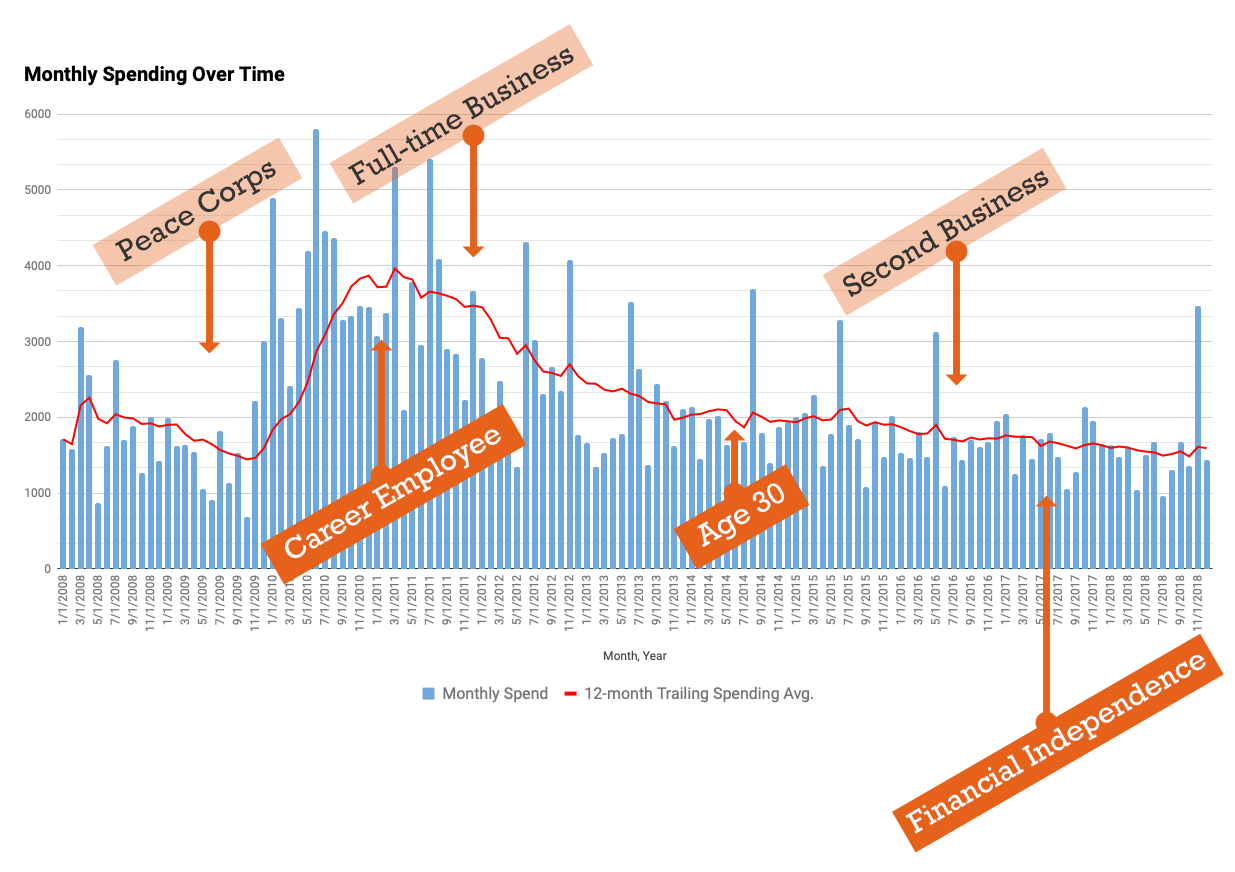

The chart above represents my personal monthly spending between 2008 and 2019.

This includes my time in the Peace Corps (the lowest spending I’ve ever tracked), my shift to becoming a career employee while living in a high cost of living city, my jump to starting my own digital strategy consultancy while working less in a less expensive area, a second business, and finally reaching financial independence close to age 33.

On first reading that you might assume my spending would spike when starting a business. It’s true that my businesses’ spending was quite high at times ($396K in 2018!). But, my personal spending only dropped after leaving the DC area and stopping my daily routine of professional wear, lunches out, and high rent. This is despite my total income actually rising beyond $100K/year in those later years.

I could certainly afford to spend more. But I didn’t.

My cost of working had cratered, returning my total cost of living to its previous normal.

Between 2010 and 2012, I spent nearly $91K in total cost of living expenses.

That’s $3,786/month. For one person.

This is what that monthly expense breaks down into, on average:

- $1,520 on rent and home expenses

- $732 on groceries, bars, restaurants

- $425 on gas, car maintenance (even commuting on public transit!)

- $390 on travel

- $171 on clothes, tech, and media

- $125 on gifts and donations

- $113 on healthcare

- $78 on movies, performances, live music

- $67 on cell service

- $165 on miscellaneous

Compare that to my portion of Jenni and I’s FIRE budget review from 2019 (which is a little more realistic than 2020’s due to the pandemic).

I tracked just under $19K in spending over 2019 or $1,563/month!

That’s less than half!

You can spot this trend developing in my spending graph above. By 2015, my 12-month trailing spending average dips below $2,000/month and continues its trend down.

The more work I’ve removed from my life (these days, hovering between 20 and 30 hours per month), the less I tend to spend. By having more time available, I feel less pressure to pay to get tasks, maintenance, and general stuff done.

I can do it myself.

Homemade meals taste better and are healthier, and I’ve got time to make them.

I have time to walk or bike instead of drive which doubles as a free workout.

I figured out how to leverage cellular MNVOs to get cheap phone service.

Jenni and I both take on more DIY challenges.

I’m willing to learn credit card rewards points systems and leverage the best redemptions to make travel cheap instead of just booking whatever is available because I didn’t have time to dig into the details.

And that’s just a few random examples of the activities I’ve taken on myself that so happen to reduce our spending. It’s just a few ways we’ve insourced our way to more wealth.

I left my $1,500/month apartment for a bigger place in a walkable area surrounded by greenery in a slower city. Instead of the glitz and glam of the Kennedy Center, we get to go to intimate performances with a few dozen audience members. $100 bar tabs turned into $10 6-packs at a backyard gathering.

Even as we close in on a $2M net worth, Jenni and I continue to spend $40-45K/year combined. That’s less than I used to spend for just me when I had a significant cost of working tacked on. Yet, neither of us feel much of an urge to spend more. And we certainly can afford to spend more.

Rather than inflating our lives with spending to bandaid over our lack of free time, we’ve built the lives we want to live—and we know how much money is enough for us to retain it.

How Much is Your “Cost of Working”?

You’ve heard that old saying that it takes money to make money. Wealth begets wealth.

But I’d like to put my own spin on it: time and energy frees prosperity.

What’s your FIRE number? If you’re still in the asset accumulation phase—the time in your life when you’re still earning big money and socking away for retirement—you might be working towards a FIRE number and date based on current spending.

But I’d like to suggest that your current spending might include a huge premium—your cost of working.

If I’d worked from my personal spending while a career employee, my FIRE number came to over $1.1M. Yet, as I’ve cut work out of my life and freed my focus to do what I want and live the life I want, my monthly expenses only need about $500K to support.

Work was costing me more than half my FIRE number.

What’s work costing you?

20 replies on “How “Cost of Working” Surprisingly Burdens Your Cost of Living”

So many people focus on cost of living but there absolutely is a cost of working. I hate having to spend money on a certain “work uniform” (button down shirt, suits, nice shoes, etc.). Feels even more arbitrary post-COVID but it’s all part of the game to look the part. Then there’s commuting costs, childcare costs, convenience costs (eg eating out more because it’s easier after a long work day/week), and the cost of your time (how much time do people spend just getting ready to go work?). It seems the additional costs in retirement get a lot of the attention (healthcare, quarterly taxes) but there’s a lot of offsetting costs related to working that go away in retirement as well. Thanks for sharing!

Yep, you hit it all, MRW! Well done.

I think the pandemic might be a little eye-opening in this regard for many people. Returning to an office after this is all over might be more unappealing than people realize—beyond the mental changes associated with being in an office. The financial costs will be more noticible once this “break” from them is over. We’ll see if some if sticks and remote work hold on in at least some places.

Then again, it’s been the “death of city” due to remote work, suburbs, the internet, etc. for decades yet just prior to the pandemic we were seeing all-time highs again in a variety of cities. People do want some aspects of being around others and the associated conveniences.

Wow, this is eye opening. I think about my life before working from home and my cost of working was huge. Gas, parking, lunch with coworkers, clothes, dress shoes, .. the list goes on. Amazing to see how working less can actually help you save.

Think you’ll wind up going back to working onsite after the pandemic? Or is that a “cost of working” you’ve permanently cut?

I’m not sure I really understood just how much I was spending to avoid any “work” beyond well, work. I skipped out on a lot of chores and tasks. I didn’t DIY as much. And now those things become little hobbies and projects, opportunities to learn, experiment, and find value in the everyday. It’s pretty amazing what happens when you don’t feel like your time is being ripped from you.

I didn’t realize how good I had it. Free unlimited personal use company car, free gasoline. Free unlimited personal use cell phone and computer. Any meals or socializing with other employees was paid for by my expense account. College scholarships for my three kids, LCOL housing eight minutes from work ran with $300 to $600 per month mortgage payment. Casual dress code at work. Air travel to nice locales with great accommodations and expensive dining. 401K match, profit sharing bonuses and lots of free company stock, medical insurance, life insurance, free training. I think work had no net cost in my case other than my time, just a lot of net benefits.

“LCOL housing eight minutes from work ran with $300 to $600 per month mortgage payment.”

Phew! I know you’re a bit older than us, but that still likely doesn’t explain that cost! Very nice indeed.

And yes, overall, you had a KILLER arrangement with your employer. I know you operated at a pretty high level, and perhaps just barely caught the tailend of the time period when employers provided more benefits. Maybe folks operating at your employment level earned similar compensation packages, I’m not sure. I know the folks operating at the level above me at my apex (and making about $500K) had a pretty sweet deal, but still not as wide-ranging as your experience!

Perhaps turning all that down shows you just how much you must value your time and who you’re now spending it with 🙂 Which, I think is awesome.

Nice post, shedding light on a (potential) major downside to work. I think this ‘cost of working’ could be very industry and job-specific. I have a similar background to Steveark, and I would say I’ve had a similar experience. A lot of my costs are paid for by the company (phone, travel, business-related meals and entertainment), and the attire in R&D is casual, so no issues there. Actually now that I’m fully remote, I don’t even need clothes! From my past work history, commuting was the biggest drag for us. At times, I was driving ~75 minutes a day, and spending upwards of $250/month on gas. My last position (prior to moving and going remote) had a 4 minute commute, and my wife’s was similarly short also, so we managed to eliminate that issue. It’s definitely good to understand all of the hidden costs of a job, though, thanks for covering this!

“Actually now that I’m fully remote, I don’t even need clothes!”

I don’t want you turning up on the news or as a meme, Adam! Careful now 😉

Yeah, back in my 2010-12 era, I could have drastically cut my expenses by living in the suburbs and commuting about an hour each way. Lots of other folks did. I was more willing to sacrifice money than time in that case, though. Hard to know what the better choice was!

That’s a crazy number for one person! I often wonder how my expenses/savings rate would be if I were to take everything down a notch and move to a low cost of living state.I feel as if I’ve finally “hacked” my hcol to get the most juice out, but it took years of working and politicking to get to this position. I wouldn’t even know where to start to try and track all the lost money it took to get to my position at work and while living in the bay area.There is a such a strong current to spend more in a high cost of living area. Everyone makes crazy money, everyone spends crazy money, its a vicious cycle that seems normal when you’re in the storm. Then there’s also the immeasurable cost, like stress related health issues, time spent commuting etc.

I’m always having a mental debate about whether to factor in my current (hcol/working) expenses into my FIRE number. To play it safe, I do use my current numbers. I figure if I can FIRE in the bay area, I should be able to move anywhere in the world to mitigate risk if the markets begin to tank or stagnate during retirement.

“I’m always having a mental debate about whether to factor in my current (hcol/working) expenses into my FIRE number. To play it safe, I do use my current numbers.”

This is smart. It might not be accurate, but it’ll be safe. If you can do any sort of transition (perhaps working in a less expensive area) or take a sabbatical, you might be able to see what your spending would look like outside the HCOL (Bay) area.

Tough to say though, so much of life might/would change if you’re in a totally different place and not working in the same way. I know mine sure did.

It’s amazing how much it costs just to live. It’s more amazing how much it costs to actually go to work and make money. The “I deserve it” attitude is the highest for college graduates who think about the past four years that they lived in poverty for.

The office politics is such a costly venture… It doesn’t cost money, it takes a huge mental toll.

David, I know when I graduated undergrad, tons of my peers went out and bought brand new cars as soon as they had their first job lined up. And lots of other spending to boot.

It was even worse when Jenni earned her doctorate. All of her peers were ready to spend. Despite the fact they were just starting and had loads of debt to paydown.

It’s understandable, but costly. And using the car example, it’s reasonable to want a reliable vehicle when you’re starting your first real job. Tough tight rope to walk!

Mental tolls…phew. That’s a whole different article about the cost of working! 🙂

Cost of working is higher than most people think due to commuting, dry cleaning, eating lunch out, and everything else that ads up. Of course some people may not have a choice.

Yep, most people need to work (and work full-time) to make ends meet. Responsibilities, hungry stomachs.

We’re lucky it’s an option.

Great post Chris! And of course… taxes!! When I shifted to part time work I calculated that my hourly rate is now significantly higher thanks to fewer days commuting, only working nights where the dress code is casual, all the time in the world to cook my own meals, being in a lower tax bracket, etc. And of course, we are now able to be at home with our daughter and don’t have day care costs to throw in.

Hey thanks Court!

And you’re right about taxes. Getting to keep more of the lower income you earn when working part-time or retiring early helps it go lots further.

Time, to your point, can do a pretty incredible job of reducing your expenses through insourcing work (especially removing convenience foods, doing your own maintenance, etc.).

This is so true! I quit working my corporate job in March 2020. My husband still works, but I earned NO income last year. It was SHOCKING how little our savings rate decreased in that year! For context, I earned almost HALF of our family’s income. It turns out that the “cost of working” (love that term) was really high for me and my stressful job! Really glad I’ve stumbled upon your blog 🙂

Glad to have you Mrs. RFL! Thanks for coming by. I’ll check out your blog 🙂

I’ve got an article coming up on this, and mentioned it in the blog, but yes—having lots of extra time (by not working) let’s you insource a bunch of activities or chores or maintenance you’ve been outsourcing and reduce your expenses. You’re effectively deciding to “work” by insourcing those things, but hopefully, as you suggested, with a lot less stress and on your own terms for what matters.

I guess nowadays, since it’s COVID times, I spend $0 cost-of-working.

Before that, I probably just spend maybe $100/mo on gas money for working.

My gig doesn’t really require me to put on a suit to work when I had to go into work, but sometimes folks would get together far bars and stuff. To my knowledge, I’ve rejected all invitations. Not because I don’t want to spend the money or anything, I just didn’t want to spend any more time with my co-workers than necesssary.

But it seems like the “cost of working” from this post is purely optional? I don’t see anything forbidding a person from setting boundaries where if a co-worker invites them to a restaurant, one could just respond with “thanks but I brought my own lunch.”

Or if someone invites a coworker to drink, just say “Thanks, but I don’t drink.” (could be a lie).

My favorite rejection to coworkers is simply “No.” One word. Without explanation. People might say it’s rude, but I don’t want to come up with any excuses because excuses = interpretations = longer conversations. “No” shuts the door perfectly.

Yep, “no” will do it for a lot of folks! 🙂 Nice to be able to do that.

Initially, you touched on the more obvious costs — things like gas. Another good example is attire.

Awesome to be able to “just work” and have it be that. As long as you can fulfill your others needs elsewhere, that’s ideal!