I have something to reveal to you. More than twelve years ago I was thinking and writing about financial independence. Sure, it wasn’t popularly called financial independence and FIRE certainly wasn’t a thing. Mr. Money Mustache had but a whisker, his moniker hadn’t been invented yet. But, I was already writing about the marginal utility of income, a subset of the law of diminishing marginal utility. It explains why each additional $10,000 of income is less valuable than the last.

I didn’t really know it, but I was setting myself up to achieve financial independence in my future even in my 20s.

I understood you should live below your means but was still trying to understand just how far below your means.

The thing is, I never published any of it. I recently unearthed some notes handwritten, some from Evernote, some from text files scattered across an old hard disk’s folder structure.

The Marginal Utility of Income

Today, I wanted to present to you one entry from early 2008. It’s about the marginal utility of income. I’ve made some grammatical tweaks, but otherwise, it’s as written in my early 20s. I hope this shares my point of view on personal finance as my much younger self. I realize sometimes it’s hard to relate to someone in their mid- to late-thirties who have already achieved financial independence.

Chris The Younger, take it away.

The Relationship Between Your Income and Its Utility

February 20, 2008

Why would someone want to make $50,000 per year instead of $100,000 per year? If everything else was equal, I don’t know anyone who would choose not to make more money. However, the math isn’t as simple as “more money equals better”. First, you should understand how income relates to your standard of living. Then, grasp how increasing income is affected by diminishing returns.

Minimum standard of living

Minimum standard of living is what it would cost for you to maintain your life at its barest necessities. This would be expenses like rent and utility cost, insurance, groceries, and so on. These are the minimum expenses you have that would keep you moving along in a reasonable, though likely pretty boring, life. For some, their minimums may include a few luxuries like their smartphone bill or perhaps less than mine – no insurance as an example.

Let’s break this down with some rough numbers for a single person living in a fairly average cost-of-living urban area, with per-month costs.

- $587 Rent – splitting a 2 bedroom

- $90 Gas/Water/Electric – shared costs

- $210 Groceries

- $36 Auto Insurance – state minimum, 1 vehicle

- $72 Fuel – largely variable, I do not drive a lot

- $154 Health/Dental – this includes insurance though I have had some significant out-of-pocket expenses

The amounts above are my actual average monthly spending levels over 2006-2008.

These are the six categories I’d be unwilling to reduce or remove unless I was in some sort of true emergency situation, so this is my minimum cost of living. It’s not a lot, less than you might guess. In fact, it’s $1,149 per month.

If you tack on an appropriate tax level, that’s about $1,417 per month in pre-tax income I would need to maintain a minimal lifestyle. That’s an annual salary of $17,004. Now, I can manage this low spending level because I have no outstanding debt and no dependents. Your situation may be very different.

Comfortable standard of living

We’ve established that I’d need to make a little over $17,000 per year to maintain my minimum standard of living costs. But that is a very skimpy and simple life. What would a comfortable standard of living look like for me?

I’d consider these expenses to make life a bit more tolerable. The amounts below are all real averages from the last year of my life.

- $184 Meals Out – fast food, restaurants, and bars

- $210 Travel – flights, hotels, and general travel expenses

- $62 Entertainment – ski tickets, theater, movies, amusement parks

With these three additional categories, I’d have more enjoyment and fun in my life. Over the last year, which these expenses represent, I’ve traveled some of Europe and taken a major ski trip with friends. I occasionally have a night out on the town. The total cost to add that to my life was just $456 per month!

Building wealth in your 20s

Combining my minimum standard of living ($1,417/month) and comfortable standard of living ($456/month) produces what I’d need to earn to continue living the happy life I have: $1,873 per month. Like my minimum budget, we can gross up that expense to figure out how much money I’d need to make in salary to cover the cost.

I’d need to earn $27,720 per year to meet my comfortable standard of living needs. The lifestyle this would enable feels like something that would keep me happy for a long while.

However, this does not include any saving or investing. Let’s add some appropriate goals:

- $6,894 Emergency Fund – 6 months of minimal living expenses

- $75,000 Investments – by 30 years old

Common wisdom is to save 6 months of living expenses as an emergency fund. For me, I’d base that on my minimal living expenses that I already outlined above. The goal would be to complete this within 1 year. That means I’d need to save about $575 per month towards this goal.

I recently read an article about recommended investment goals by age. The suggestion, based on government income data and savings information, set a goal of just under $75,000 for someone 30 years old in the United States. Considering that’s about 6 years in the future for me, I’d need to save and invest about $12,500 per year or $1,042 per month.

The emergency fund goal needs to be grossed up again to account for taxes, so that’s $709 per month. My investment goal would be split between an IRA & 401k as well as a brokerage account. I’ve already been making investments in individual stocks (2020 ed: that was a big mistake!). The amount in the brokerage ($521) would need to be grossed up, which comes to $643 per month. We’ll assume I’ll drain the emergency fund about once per year.

- $709 Emergency Fund

- $643 Brokerage Account

- $260 IRA

- $261 401k

That brings my total savings goal to $1,873 per month while accounting for taxes. That represents $22,476 in salary per year. Added to our comfortable living standard, we reach a total income goal of $50,196.

Diminishing returns of increasing income

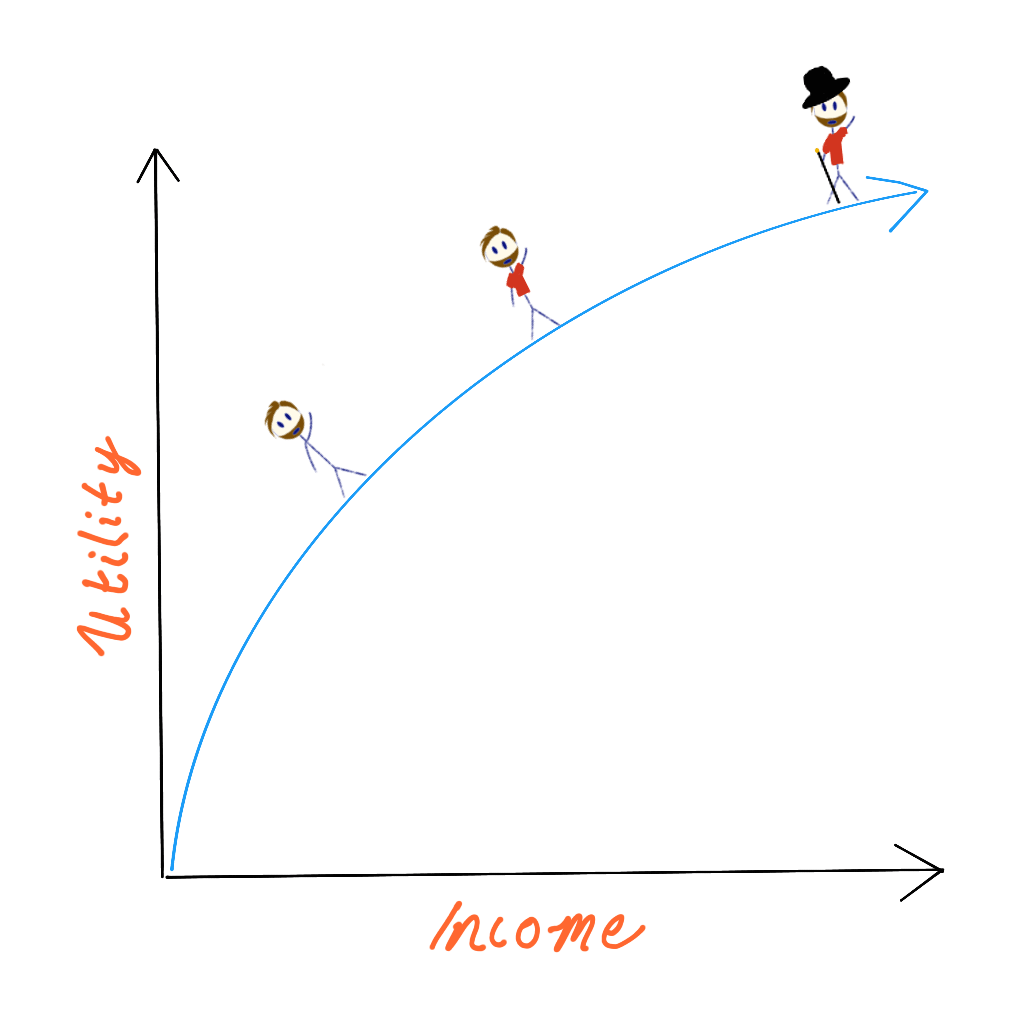

In my personal case described here, we’ve worked through three levels of annual income:

- Minimum standard of living: $17,004

- Comfortable standard of living: $27,720

- Fulfilled standard of living: $50,196

In the case of minimal living, all of those dollars are incredibly valuable to me. I need them in order to meet my minimum standard of living. It’s to have a secure place to sleep, food, pay the utility bill, maintain my health, and transport myself for work.

The extra $10,000 or so necessary to reach comfortable living is a bit less important, but still very valuable to me. They allow me to be a happy, well-adjusted person with fulfilling elements to my life like travel, culture, and social fun. While still very important, they’re not life sustaining. In tough times, I could cut some of these expenses. The extra income isn’t as necessary and I don’t derive quite as much value from these dollars as I do in the case of minimal living.

Lastly, we reach a complete, healthy budget at just over $50,000. My fufilled standard of living. My salary accounts for all my minimal and comfortable living expenses as well as saving for my retirement future and building a healthy emergency fund. It allows me to reach investment goals experts recommend to safely be ready for old age. These are funds dedicated to my future. Compared to the comfortable level of spending, these funds are much more flexible since I won’t even see their effects except in emergencies and far in the future. These extra $23,000 dollars have less value since they’re less pressing than the previous $27,000. The extra income has significant diminishing returns. Still, they let me build towards a successful future.

But what about another $50,000 if I had a $100,000 income like discussed in the introduction? What would I do with that money?

I could change my life around a bit. Maybe I’d buy a nicer car. Perhaps I’d bump my travel style up a level. But really, what would I get out of that? Doubling my salary would likely mean doubling my responsibility, workload, or stress. And what would I do with that extra income? I’d perceive very little extra value from it but the effects on my health and mental wellbeing would be noticeable if my workload doubled. This extra income has greatly diminishing returns but the negative impact of work on my life is linear.

The amount of comfort I have in life with my comfortable living income level keeps me happy. Doubling my workload in exchange for an even more cushy lifestyle doesn’t sound like a good proposition to me. I trade time for money directly as a contract worker. There’s a linear relationship between how much time I spend working and how much money I make. I wouldn’t want to give up twice as much time in exchange for that slightly cushier lifestyle.

I’ll take the $50,000 salary.

Back to current times in 2020 with Chris the less Young.

Diminishing marginal utility of income

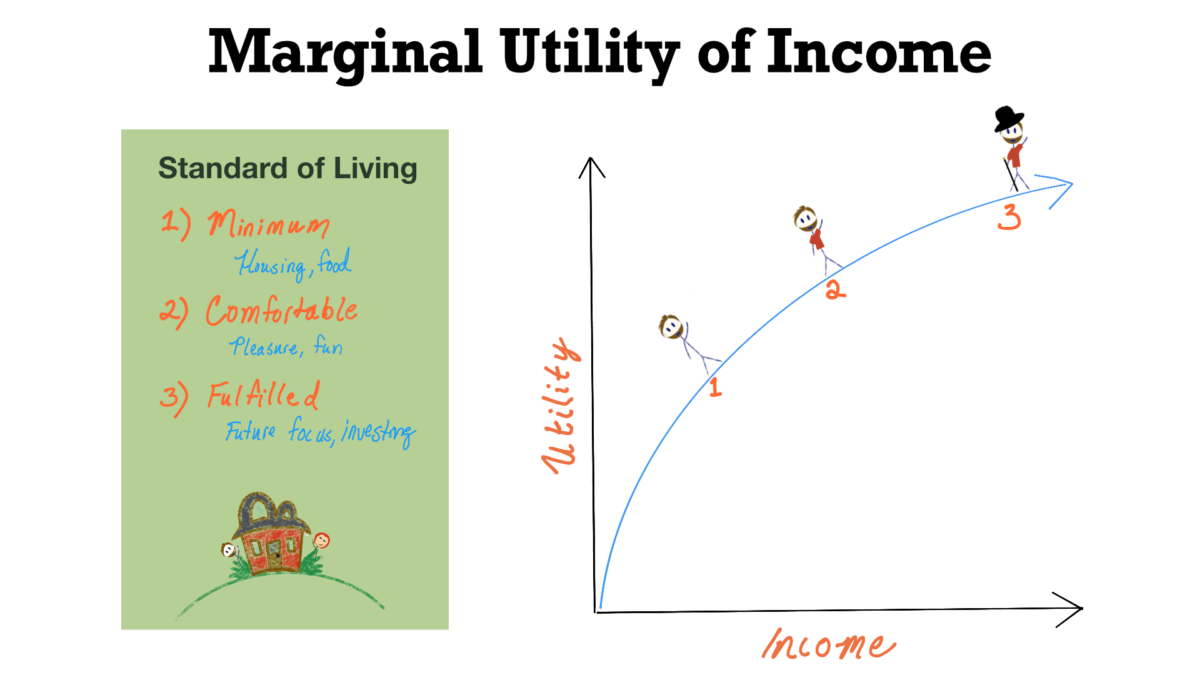

What do you think about the three levels of standard of living I created as milestones back in 2008? I wasn’t familiar with the term then, but the concept I was attempting to explain is the marginal utility of income. It piggybacks on the law of diminishing marginal utility. Let’s peel back those layers to understand these economic concepts and how they apply to my income situation at 23 years old.

Marginal Utility is an economics term that describes the value a person gains from consuming more of a service or good. Utility is simply the value of a single instance of consumption whereas Marginal Utility refers to each additional instance and the relationship between those instances.

The law of diminishing marginal utility is an economics term which describes the decreasing value a person gains with each additional action of consumption for a good or service.

I thoroughly enjoy dark chocolate. I like to have a small piece of a bar each day. The first bite is always the best when I’m craving it. Sometimes I mindlessly eat more than just a small bite. As my taste buds are saturated in the rich flavor and I’m satisfied, each additional bite provides me with little extra pleasure. I’ve eaten more than half a bar before and sometimes feel a bit sick for it. It’s a moment of losing the ability to enjoy the small things. Not only has my value obtained from the chocolate diminished with each additional unit of consumption, but it’s even started to have a negative effect. Spending on chocolate now has diminished marginal utility for me.

The marginal utility of income is the relationship between the change in utility of a unit of income as that income increases or decreases. Typically, the utility of an additional unit of income decreases with each additional unit but this is not always the case.

If $50,000 of salary covers all of your standard of living expenses, increasing your salary to $100,000 of income may be less valuable to you than the initial $50,000 as you spend the increase on luxuries rather than necessities. The story above from 2008 is an example of the marginal utility of income.

Do you think that my concept of three levels of standard of living (minimum, comfortable, and fulfilled) represent distinct levels of the marginal utility of income? They tie in well with the steps to financial freedom. The utility of extra income tends to decrease with each additional dollar earned.

Happiness as a function of income

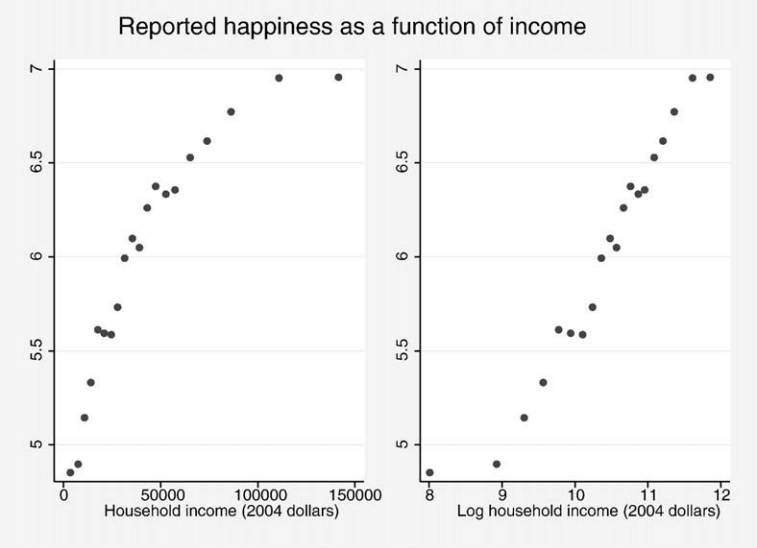

As income increases and its marginal utility decreases, so too does its value to our happiness. This ties in well with the marginal utility of income since much of the point of increasing income is to increase happiness.

A recent study in the Journal of Public Economics attempted to survey and report the relationship between happiness and income, globally.

As you’ve probably read before, happiness and rising income tend to disassociate once you’ve reached a “middle class” income in the developed world.

This study analyzed a global population and found that the dispersion between income and happiness increased for all populations similarly: it’s not related to a specific culture’s society or governing style.

Here’s the key graph from the study:

During my research for this piece, I was surprised to find just how quickly happiness rises for very low incomes. Lifting someone up out of poverty does correlate pretty strongly with increasing happiness.

The relationship diverges pretty strongly as happiness flattens. In my view, that’s just another reason fairly high earners should strongly consider the value of time as they decide what to spend their money on.

How to Build Wealth in Your 20s

Twelve years later and my actual spending hasn’t really changed (mind you, we’re comparing a solo Chris versus Jenni and I both these days). The marginal utility of income for me beyond the “comfortable” standard of living was solely to accelerate our attainment of financial independence as we became millionaires by 33.

I never did decide to buy that much nicer car or switch to five-star hotels in my travels even once we could easily afford it. We didn’t use our increasing income over the years to inflate our lifestyle. Instead, we traded not spending the extra income for more time in our lives as we valued time more than spending.

If I could address my younger self and teach him how to build wealth in his 20s, I’d make one significant change. Rather than buying those individual stocks, I’d tell him to focus on investing in simple index funds like VTSAX or VTI.

If you’re in your 20s: have you thought about the marginal utility of income and how it applies to potential lifestyle inflation as you get older?

If you’re older and on the way to FI (or already there!), how has your spending changed as your income changed?

Let us know in the comments!