Being a specialist vs generalist has its pros and cons. Specialists can earn more money and recognition in their niche, but they may also face more competition and less flexibility. Generalists can adapt to different situations and opportunities, but they may also struggle to find focus and their identity.

Jenni and I have a lot in common, but also have one big difference: she’s a specialist and I’m a generalist. She’s an expert in Pharmacy, while I have a mixed range of knowledge. We often chat about how this affects our career and life paths.

But the choice between specialist vs generalist goes beyond your work. It also influences your lifestyle, hobbies, and relationships.

- How do you spend your free time and money?

- In what ways can you build community and share your interests?

- How do you cope with change and uncertainty?

This is especially relevant if you’re pursuing financial independence and early retirement–FIRE. Should you specialize in a high-paying niche or diversify your income streams? Should you invest in your skills or explore new domains?

In this post, we’ll share our personal experiences as a Specialist and a Generalist, and help you find the best fit for your personality and aspirations. We’ll also show you how to achieve the optimal balance for your FIRE path.

Specialist vs Generalist: Master of One vs Jack of All?

A common saying to describe the differences between a specialist and a generalist is “a jack of all trades is a master of none”. While it’s accurate to boil the differences down this way, the phrase is typically used in a pejorative way.

Becoming a master is what we seek—the specialist.

The simple Jack, a mere generalist, doesn’t understand the inner workings of the world.

Arguably, our educational system is built upon the premise that we need to become masters. Primary school exposes us to many topics with superficial understanding, but secondary school is entirely about becoming specialists.

How often do you find pupils that seek to earn degrees in multiple, disparate fields? It’s a rarity. Instead, our society drives us to earn a bachelor’s degree and niche down to a master’s. Then the challenge is to see if we have the talent and persistence to achieve the ultimate level of education: a Ph.D., the true expert in their niche.

Seeking to become a generalist died out around the era that the “Renaissance Man” implies.

Leonardo da Vinci isn’t who we seek to emulate.

Instead, it’s the specialists—Olympians, rock stars, Nobel laureates, and brain surgeons.

They’re called Jedi Masters for a reason. We’re taught to aim for the pinnacle of specialization.

Comparing Generalist vs Specialist

If we can accept that the modern world, our current society, pushes us towards specialization…what does that mean for the generalist? And is it really the case that one is better than the other?

The pros and cons of being a specialist or a generalist

Let’s start by breaking down what a specialist and a generalist are when it comes to a typical education and career path. We’ll work through the pros and cons of each as well.

Specialists: Experts in their fields

Specialists are people with a deep interest in pursuing the finer details of any particular topic. They want (and need) to understand the inner workings of their niche. They seek to understand all approaches in their area of expertise.

A specialist is a person who is highly skilled within their specific, and often restricted, field.

The benefits of specialization

- The authority. A specialist tends to have worked within their field since they were young, beginning with early and ongoing education. They not only understand the current best practices within their field but also the history of change over time. Specialists tend to be the final decision-maker.

- The mercenary. Specialists are often in demand from multiple sources as few can attain their level of knowledge. Organizations understand the role specialists play and what to expect of them. For jobs with specific criteria and guidelines, hire a specialist. They rarely require on-the-job training.

- The non-negotiator. When you carry the weight of being the expert, the only person with a solution to a particular problem—you don’t have to negotiate. You more often get to set the terms of the deal. Somewhat common and exceptionally high-paying jobs tend to be specialists: neurosurgeons, investment bankers, and corporate counselors.

How to become a successful specialist

Jenni and I watched El Camino last night—it’s the movie ending for TV’s Breaking Bad. *Spoilers ahead*. The star, Jesse, needed to escape the life he had. A new identity, new location, new everything. And he knew a fixer that could do it.

In a previous situation, he went back on a deal with the same fixer. But now he needed him more than ever. And he knew the price:

$125,000.

He took a chance to earn the money he needed and successfully turned up $248,200 to start his new life. He went to the fixer. There was one problem.

The fixer told him he’d need to pay for the first deal he backed out on years before.

And he’d need to pay for this second chance. $250,000 total.

Jesse was just $1,800 short. Jesse pleaded with him over the small difference and even threatened him. But the fixer did not budge.

The fixer was the specialist. He was the only person with this particular set of skills Jesse needed.

A specialist can set their own price.

The drawbacks of specialization

- You’re too big for my problem. For niche problems, call the specialist. When you need to recaulk your bathroom tub, you call a handyman (or better yet, don’t fear trying to do it yourself!). Sure, a professional licensed plumber could caulk a tub. But you save the plumber for the more serious jobs! This happens just the same in the workplace. You don’t ask the divorce attorney to file briefs, that’s what the paralegal does.

- You’re no longer needed. Made redundant. Obsolete. Algorithms, automation, or plain societal shifts put specialists at risk. They work within clear boundaries with defined rules and systems for their field. That’s the sort of thing that is easiest to replace with a robot or code.

- A little of this, a little of that. Part of the appeal of a specialist is to have someone who knows all the finer details of a topic. But in order to achieve that level of knowledge, the specialist often sacrifices skills in other areas. This can be a problem if an organization can’t quite fill the time of a specialist’s workload within their niche as the specialist may lack other useful skills to maximize their remaining workload available.

Now that we understand the pros and cons of being a specialist, what about a generalist?

Generalists: Adaptable and versatile

Compared to specialists, a generalist tends to see problem areas from a higher perspective. They’re the folks that understand multiple pieces to the larger puzzle even if they’re not quite sure how any individual piece functions discretely.

A generalist is a person that has general knowledge—some competency—in several different, though often related, fields.

The benefits of generalization

- The prospect. A generalist is open to the possibilities. They’re malleable and take on what may come. The raw talent that recruiters search for is the generalist. New challenges that stretch their comfort zone are appealing to them. As a generalist, they can join an organization and test the waters to find new roles or leadership positions to take on depending on their mixed skillset and the needs of the organization.

- The hatter. You might recoil at the phrase “wear many hats” depending on your personality. It means you’ll be dabbling in various tasks and responsibilities for a job. You might need to know how to lay out a newsletter in design software, write copy for the structure of the content, and manage the system that sends it out. Large organizations have the budget to have individual specialists handle discrete task areas. Small organizations frequently have to use a single generalist to cover several tasks.

- The leader. While specialists might make up the bulk of the high performers, they often don’t appear frequently at the very top of org charts. Leadership positions need a divergent set of skills. Specialists frequently leave social communication to wither. That big-picture view comes in handy when you’re managing all the moving parts of an entire organization.

The drawbacks of generalization

- Always the student. Virtually by definition, a generalist will always be a student. As they encounter new problems adjacent to their current knowledge, they don’t limit their experience to what they already know. Rather, they seek to understand and solve those problems adjacent to what they’re familiar with. They’ll always be a student, guided by the experts within the new areas they seek.

- The coffee (person). The value of a generalist’s skill is frequently unseen. A generalist does have knowledge in a variety of fields. But, sometimes it’s hard to make this knowledge apparent without a specific headline or descriptor for their skillset. Often they’re a square peg trying to find a fit in a round hole. Because of this, generalists might find that leadership has them doing unskilled work to simply make use of their time.

- Typecast. Somewhat confusingly, a generalist might find that they can’t become a specialist if they so desire deeper learning on a particular topic they’ve come to enjoy. An organization might simply hire a specialist on a temporary basis to resolve a deeper problem beyond the generalist’s capabilities rather than expend the resources to train the generalist.

How to become a well-rounded generalist

Personally, I consider myself to be more of a generalist at this point in my life. I have a liberal arts degree in a field I haven’t ever directly used professionally. The first decade of my professional work straddled creativity, marketing, and information technology.

I’ve never wanted to be stereotyped as having a specific and singular skillset. I’ve used FU money in a clear way to make my own exit twice in my working life. I shared about the first time—when my potential employer attempted to force me to cease my side business.

The second time I leveraged FU money was years later when the current division my team worked within was going to be absorbed by a different group within the larger org chart. I would no longer work in marketing & communication. Instead, I’d work in information technology.

So I quit.

Why? Because I wanted to protect my ability to work across different disciplines. If I went into IT, I might make more money—but it’d be at the cost of becoming an expert in a narrow field.

That ended up being my last position as someone else’s employee.

I considered one other position that could have really slapped the golden handcuffs on. My post on negotiating pay effectively discusses this.

I turned down a $175K salary at 27 years old. Instead, I left the city I’d made home to reinvigorate my own consultancy I’d protected the first time I doled out the FU money.

And since 2013, I’ve been the many-hat-wearing, multi-business-owning generalist that’s left me with novelty and challenge to find satisfaction within my work.

How to choose between being a generalist or a specialist

Now that we’ve looked at the pros and cons of a generalist vs specialist, where does that leave us with an understanding of which is better?

The purpose of this post isn’t to define whether a generalist or specialist is better, whether for your career or even life in general. Rather, it’s to compare and contrast the two avenues you might choose.

Will you develop a wide or deep skillset?

Defining what’s better is a matter of figuring out what is better for you. Not for everyone.

You.

Ultimately, there are two additional parts to the puzzle that are important to understand when trying to figure out whether being a specialist vs generalist is right for you.

First: you might shift from one to the other over time.

Second: I believe it’s not binary. There’s a spectrum between being a generalist and a specialist.

From Generalist to Specialist and Back Again

I don’t think we are all, individually, generalists or specialists throughout life. It isn’t an inflexible character trait. In fact, I’d like to argue that it’s a state we should endeavor to transition between.

My personal journey as a generalist and a specialist

Start wide. If you’re just starting out in your journey, perhaps while in secondary education, go wide in your consumption of the world’s career tracks. Learn a little about a lot of different things that interest you. You’ll become a generalist for the first time.

Learn enough to earn. When one of those interests really grabs you—whether that’s photography, investing, or art—pursue it enough to earn a living from it. This is the strength that you can sell at the start of your career or even create a business from. This is your opportunity to become a specialist and reap the rewards of being one.

Protect your options. But don’t let this pigeonhole you. Keep learning new things. Often, learning new things will let you find connections between fields that specialists within that can’t see. This can give you the creative insight you need to set you apart from your peers.

How to expand your skill set and knowledge base

With success and stability, you might find a desire to explore more in life. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into a business. Perhaps you want to consider early retirement.

In either case, for success, it’s the ability of a generalist that is needed.

If you start a business, you’ll need to:

- Understand how to create a business plan

- Come up with creative ideas to market your product or service

- Manage the operations and logistics of the business

- Provide customer or client service

- And so much more!

You’ll be that hatter I mentioned before. Your skill set needs to be wide, though not terribly deep, to handle the initial phases of starting a business.

How to enjoy retirement as a generalist

I’d like to make a similar argument for those contemplating early retirement (which is what Jenni and I are working through now).

We have a lot more time on our hands these days. We’re transitioning to early retirement and are currently semiretired. And to be clear, this extra time is one of the major benefits of working part-time.

But, time does need to be filled with something.

What will that something be? Do you fear your ability to enjoy retirement and worry about feelings of being useless to society?

The most natural way to counteract that is…well, to feel useful to yourself! It’s to find a plan for your own life, to lay out your own markers for success, and come up with creative ways to fulfill those needs.

It’s just like being a generalist in your own startup—your life after work. You need a mix of skills and interests to be successful in this phase of life.

It’s this transition from generalist when young and developing your skills, to a specialist in your prime earning years, and back to generalist to find different areas of fulfillment later in life that I think is the most valuable nugget of insight from my discussion about generalists vs specialists with Jenni.

Life is more exciting when you can do a variety of novel things. Having a mixed set of skills is a good plan.

But, when it comes to building your wealth, it’s smart to be really good at something.

There are a lot of specialists out there earning great wages. And while the top-tier folks tend to be generalists, there are not very many of them.

Sometimes aiming for “enough”—not more—is the smarter move. There’s a time for taking risks in life.

Beyond the Generalist-Specialist Dichotomy

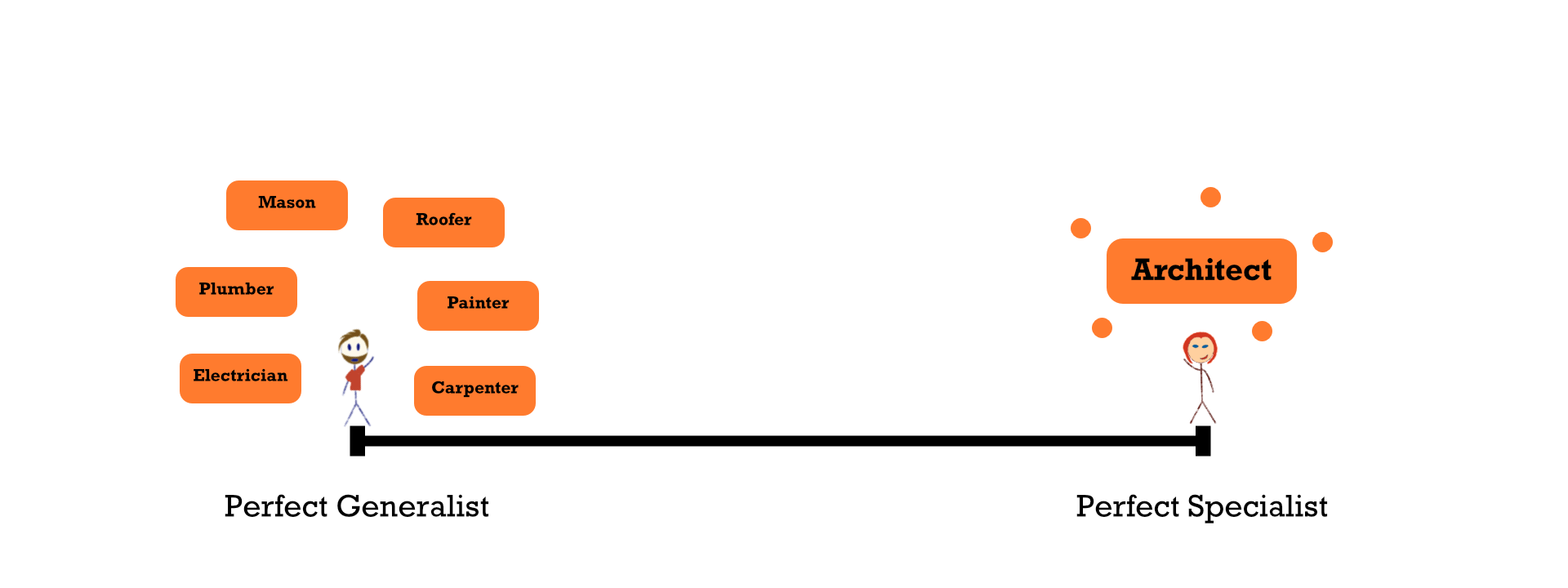

And for our last piece of the puzzle. I believe there’s a spectrum between being a specialist and a generalist.

Although this article examines the specialist vs generalist comparison as if they are dichotomous, I believe that people do not neatly fit into one singular category in a binary manner. Just like we don’t have perfect introverts or perfect extroverts, most people fall along the spectrum between being the idealized specialist or generalist.

At the extremes, a perfect specialist would know all there is to know about a singular topic. They could be a master architect, capable of designing all manner of construction. They could just as easily design the most structurally sound bridge as they could the most energy-efficient house.

But, they would also know virtually nothing about anything else. They’d have zero knowledge of social hierarchies or business practices.

Similarly, the perfect generalist would know a little about everything. Taken to the extreme, it’s safe to assume that the world’s knowledge couldn’t fit inside one person’s memory so they’d wind up knowing very little about millions and billions of topics. Perhaps they could fit a single fact about nearly any field in their brain, but nothing more.

As you might imagine, in either case, the “perfect” version of a generalist or specialist would be nearly useless. They wouldn’t be able to operate in our world on their own.

Finding the right balance for your career and life goals

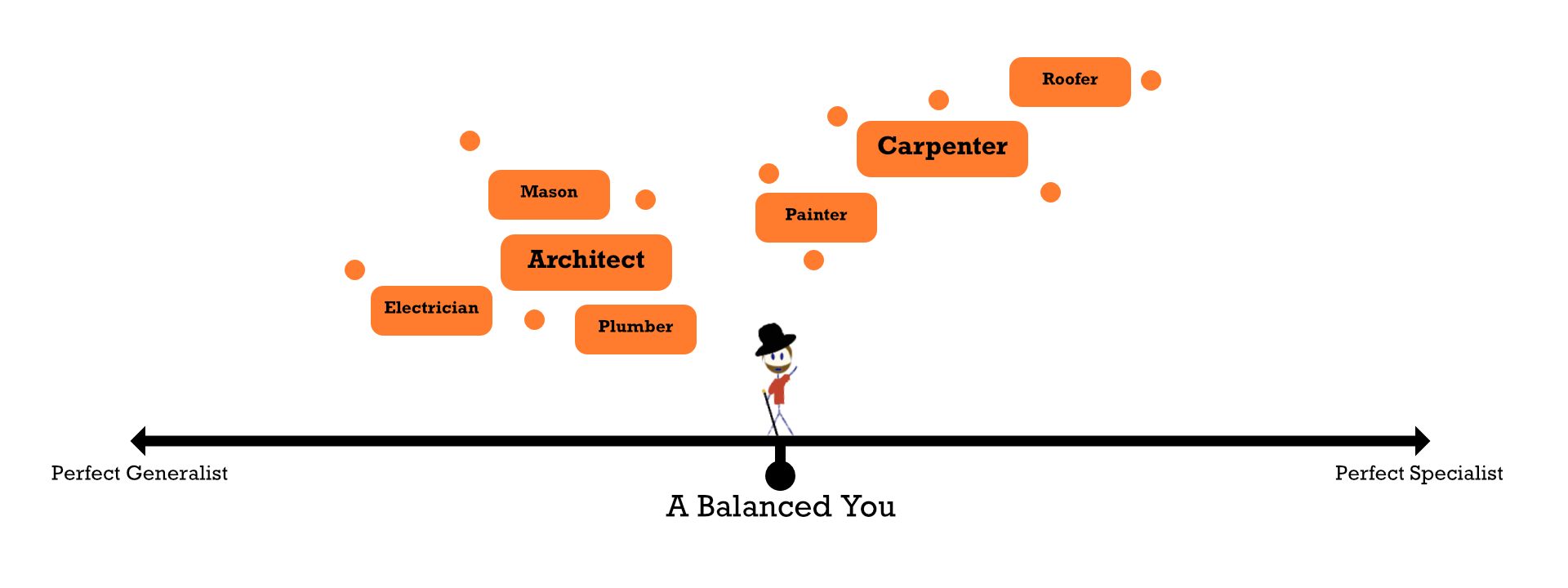

Connecting to the first piece of the puzzle—shifting between generalist and specialist over time—I’d like to offer up the idea that we should seek to find a balance of being both amateurs and near-experts in many fields.

Maximizing the value of your ability to be both specialist and generalist can come from applying the 80/20 rule (Pareto principle) to seeking expertise. True expertise comes from applying huge amounts of effort and energy to becoming a master. But, you might be able to attain 80% of an expert’s knowledge with just 20% of the effort. It’s that last 20% that takes up all the effort.

If you attain near-expert knowledge in a handful of fields (rather than true expertise in a singular field with the same total effort), you’ve opened the door to cross-disciplinary ingenuity and creativity. It’s what usually takes multiple people working closely together to achieve.

The power of interdisciplinary thinking and learning

All too often, breakthroughs hide behind experts in silos unable to communicate with each other or outright disinterested in the other’s field.

There are new and ongoing studies about how interdisciplinary research can produce better outcomes:

Addressing many of the world’s contemporary challenges requires a multifaceted and integrated approach, and interdisciplinary research (IDR) has become increasingly central to both academic interest and government science policies.

“Interdisciplinarity revisited: evidence for research impact and dynamism” [Source: Nature]

The study in Nature found that increasing the number of disciplines by even just one led to a 20% improvement in research impact!

By finding a balance of multiple areas of interest in life, you can create the same sort of advantageous cross-pollination for yourself.

Key Takeaways for Being Both a Generalist and a Specialist

Being a specialist vs generalist is not a binary choice. You can switch between the two roles depending on your goals, interests, and circumstances. Both options have their advantages and disadvantages, and finding the right balance is key to your career and life satisfaction.

In our younger years, being a generalist lets us be exposed to a great variety of life. It gives us a chance to find out how our talents apply to the world.

In our prime years, we can approach specialization to maximize our earning potential. It might be your key to financial independence.

But as we reach closer to mastery, time invested in our specialty earns diminishing returns. In our later years, as we approach retirement, that time can be better invested in becoming a generalist once again.

By bringing novelty, challenge, and new interests back into our lives we’ll have a chance at finding new areas of deep interest once again in our later years.

But this time, it won’t be for financial gain.

This time, being a generalist will be for ourselves. To create a fulfilling life full of challenge and unusualness—a key to enjoying retirement.

In your current stage of life, do you think you’re either specialist vs generalist?

Do you think that our personality drives us to be more one than the other?

Let me know your thoughts in the comments!

6 replies on “Specialist vs Generalist: Picking Your Career and Life Path”

This is a good one, Chris. In my professional life, I know for sure I’m a generalist striving to become a specialist. But maybe specialist isn’t the right word, I’m striving to become an “expert” or seasoned generalist haha. In my line of work I hire a bunch of specialists to perform their work and my job is managing the “experts” in their particular field. There is definitely a craft to knowing just a little bit of everything so you aren’t fooled and can make fast decisions. A carpenter is a great example of a generalist. He has a tool box and can apply the tools and building knowledge to build anything so long as he has plans and material. But he can’t properly or legally engineer the design of a building–he might think he could, but it’d be against the law. And laws play a big part in the power of the specialist.

There are times when I feel like I’ve jumped around too much and haven’t become an expert in anything. But I’ve noticed I’ve been able to leverage this “been around” experience and use it to my advantage. My generalist expertise has come in the form of how I deal with people. I take great pride in influencing the difficult personalities of specialists.

I, for one, really like the idea of the renaissance man. I think the key to this is having the time to pursue many things. Something a lot of the 9-5 people don’t have. This is what makes FIRE so lucrative to me. It’s the idea that you won’t be wasting time trying out new things. I need to look up the Pareto Principle…sounds intriguing.

Great post Chris! Looking forward to reading about your generalist pursuits in retirement!

It might why I relate to and enjoy your story, Noel. Our work is definitely it different fields but I suspect we do similar things.

I was thinking of how to phrase what I did for work, within the context of this article, when writing it. The section got cut (it was already a really long post). But, I described it like this:

The best way to think of what I’ve done for work is to relate to a general contractor. They frequently know how to do a bit of all the physical trades they work with and they understand the larger planning, blueprints, regulations, and requirements. They know how to communicate with the customer directly and provide service. But their real value is being able to connect the different professions and client together—to be able to translate the architect’s blueprints for the mason’s construction. They can understand the ideal recommendation the roofer makes but convey that to the customer as a set of options with the different trade-offs.

This is basically what I did—a general contractor for the web. I’ve worked on native device apps (think smartphone apps), websites for consumers (the marketing side), web applications for discrete functions (often business apps), newsletters (where larger organizations dump a lot of resources into this marketing element), and design systems (the discrete user experience side of a digital product). And I’ve done it via local small business, international enterprise, higher ed, and government. All these different contexts have wildly different requirements and underlying technologies. But I’ve always sat in between the technology and the business—marketing and information technology. It’s meant I’ve been exposed to a ton of different digital tech, I’ve had lots of novelty to become more of a generalist over time.

And I’m with you with FIRE and the potential time it frees up—I really like the idea of becoming more of a renaissance man as I get older. I thoroughly enjoy learning how different things work in fields I’m unfamiliar with. Will I become in an expert in any of these topics? Probably not. But that’s not the goal—I don’t need to make money or a name for myself through them. They’re for the pleasure of learning and experimenting. 🙂

As for the Pareto Principle.. I shouldn’t have assumed readers would be familiar! It’s a really fun concept that shows itself in myriad different ways across life. You might also know it by the “80/20 rule”. 20% of the effort produces 80% of the results. I’d guess I first read about it in the 4-Hour Workweek (Tim Ferriss). This is a good rundown on it:

https://betterexplained.com/articles/understanding-the-pareto-principle-the-8020-rule/

Great thorough post. I’m at a spot where I now dislike having to think about whether I should go generalist versus specialist based on someone else’s needs. I wish I was at a spot where I could choose because I want to be either, not because someone else needs me to be one.

I LOVE that you finished watching El Camino! I thought it was a bit too slow versus the Breaking Bad universe but it was still great. I had no idea the actor who played the fixer died of brain cancer and he actually didn’t get to see himself on the debut day, I believe.

Also finally, the complete saying is “a jack of all trades is a master of none but oftentimes better than a master of one” 😉 No one really says that though, but just as an FYI!

Hey David!

That’s a difficult position to be in. Hopefully you can ride the specialist wave to higher earnings and maybe with employer-sponsored education/certification at least.

Yea, El Camino was a great closing for Breaking Bad. Tied things up nicely.

I didn’t know that was the full quote! Thanks for sharing 🙂

Being above average at many things is good in life but bad at work. It is much better to be known for something at work.

Yep, being a specialist at work lets you become “that guy/gal” for particular problems, something to remember you by.

Unless you’re on a leadership track, I think being a specialist for work purposes makes a lot of sense. Though it’s often the generalist that brings disparate skills (and people that represent them) together to bring life to novel ideas, they’re often the leaders. And that is their skill.